An Excerpt from the Safar-nama of Nasir Khusraw:

“As I have already stated, the Ka‘ba is situated in the middle of the Haram Mosque, which is in the middle of the city of Mecca. It runs lengthwise from east to west and the breadth is on a north-south axis. The walls, however do not meet at right angles, for the corners are rounded so that the whole is an oval shape because when people pray in this mosque they must face the Ka‘ba from all directions. Where the mosque is longest, which is from Abraham’s Gate to the Bani Hashim Gate, it measures 424 cubits. The width at the widest point, from the Council Gate on the north to the Safa Gate on the south, is 304 cubits. Because of its oval shape, it is narrower in places and wider in others.

Around the mosque are three vaulted colonnades with marble columns. In the middle of the structure a square area has been made. The long side of the vaulting, which faces the mosque courtyard, has forty-five arches, with twenty-three arches across the breadth. The marble columns number 184 in all and are said to have been commissioned by the Baghdad Caliphs and to have been brought by sea from Syria. The story goes that when these columns arrived in Mecca, the ropes that had been used to secure the columns on the ship board and onto carts were cut and sold for sixty thousand dinars. One of the columns, a shaft of red marble, stands at the spot called the Council Gate; it is said to have been bought for its weight in dinars and is estimated at three thousand maunds.

There are eighteen doors in the Haram Mosque, all built with arches supported by marble columns, but none is set with a door that can be closed. On the eastern side are four doors. Set in the north corner is the Prophet’s Gate with three arches. On this same wall in the southern corner is another door also called the Prophet’s Gate. There are more than one hundred cubits between these two doors and the latter has two arches. Exiting by this door, one is in the Druggists’ Market, where Prophet Muhammad’s house was. He used to come into the mosque to pray by this door. Passing by this door, still on the east wall, one comes to Ali’s Gate, through which Ali, the commander of the Faithful, used to enter for the prayer. This gate has three arches. Past this is another minaret, to which one runs during the Sa‘y from the Bani Hashim Gate and which is one of the four minarets previously described...”

Source: Thackston, W. Wheeler McIntosh, ed. trans., Nasir- i Khusraw’s Book of Travels (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2010), 94–96.

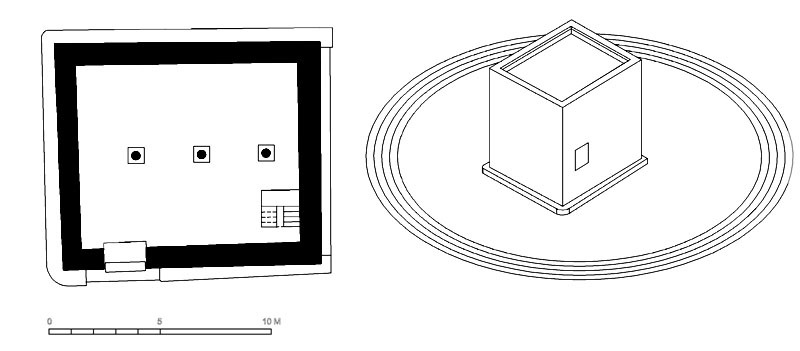

Mecca has been deemed a sacred site since ancient times. Located in the Hijaz, about 72 km inland from the Red Sea port of Jidda, Mecca lies in the centre of a wadi or valley, between two ranges of bare, steep hills. The lower part of the wadi is al-Batha’, where the Ka‘ba, the principal site for the annual hajj (pilgrimage) of Muslims, is located. Originally the Ka‘ba was surrounded by houses close by, but there was always ample free space around it. Over the course of centuries, the area around the Ka‘ba has been extended to constitute the present mosque.

The location of Mecca makes it a favourable site as a trade centre. Important routes from Mecca lead in the north to Palestine and Syria (Gaza and Damascus); in the northeast to Iraq through Jibal al-Surat; in the south to the Yemen and in the west to the Red Sea. Rainfall in Mecca is scant and irregular, punctuated by years of no rain or violent torrents concentrated within a short period of time.

The beginning of Islam in Mecca: Mecca was the birth place of Prophet Muhammad. He was born into an influential trading clan, the Quraysh, who were also the caretakers of the Ka‘ba. Prophet Muhammad received his initial revelations during one of his retreats in a cave of Mount Hira on the outskirs of Mecca. Many of the Qur’anic verses that were revealed in Mecca call attention to the moral, social and spiritual decay in Mecca as a result of various factors, including the great increase in material wealth. Later, the Prophet migrated to Medina, but travelled to Mecca for pilgrimages. Mecca has thus been of central importance to Muslims throughout the history of Muslim civilisations.

Mecca during the Caliphates: Following the demise of Prophet Muhammad, the military expeditions and resulting conquests of lands to the east and west of Arabia led to the development of new political and religious centres in the Muslim world. The Umayyads established Damascus and Jerusalem as their political and religious centres while the Abbasids established themselves in Baghdad. However, Mecca retained its religious importance as a pilgrimage site for Muslims at all times. The Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 170-193 AH / 786-809 CE) is said to have expended vast sums in Mecca on his nine pilgrimages. However, with the decline of the Abbasid caliphate, after the death of the caliph al-Ma’mun (r. 197-218 AH/813-833 CE), a period of anarchy began that was frequently accompanied by scarcity or famine. For a number of rulers, it became regular custom to be represented in the low lying grounds of mount Arafat and to have their flags unfurled. These trends severely affected the safety of the pilgrim caravans.

The Rise of the Sharifs: The Sharifs were the descendents of Hazrat Hasan b. Ali b. Abi Talib and their position symbolised the relative independence of western Arabia from the political and religious life of the rest of the Muslim world. After the founding of the Sharifate around 357 AH / 968 CE, Mecca took precedence over Medina. The strength of the Meccan Sharifate became evident when, in 365 AH / 976 CE, Mecca refused to pay homage to the Fatimid Caliph. Soon after, Mecca lost all imports from Egypt. This forced Meccans to give in as the Hijaz was largely dependent on Egypt for its food supplies. In the 6th AH / 13th CE century, Qatada b. Idris, who enjoyed the support of the notables of Mecca, attempted to establish the Hijaz as an independent municipality; however, as several rival political forces intersected on Hijaz, Qatada did not succeed in his ambitions.

The post-Mongol period: In 656 AH / 1258 CE, the Mongols conquered Baghdad and ended the Abbasid Caliphate. From then on, the pilgrim caravan from Iraq no longer held the political significance it had once enjoyed. In Egypt, power passed from Ayyubids to the Mamluks. Mamluk Sultan Baybars (r. 658-76 AH / 1260-77 CE) soon became the most powerful ruler in the Muslim world. He left governance of Hijaz in the hands of the Sharif, Abu Numayy, who firmly ruled Mecca during the second half of the 7th AH / 13th CE century.

Mecca enjoyed a period of prosperity under the Sharif Malik al-Adil b. Muhammed b. Barakat, whose rule (r. 859-902 AH / 1455-97 CE) coincided with that of Sultan Qa’itbay in Egypt. The latter has left fine memorials in the form of buildings that he had erected in Mecca. Under Ottoman protection, the territory of the Sharifs was extended as far as Khaybar in the north, to Hali in the south and in the east into Najd. However, the Hijaz remained dependant on Egypt not only for its food supplies but also for the political and religious direction. But with a strong government in Constantinople and its patronage of the various religious and educational establishments, the dependence was less perceptible.

Nineteenth-century descriptions of the life in Mecca: We owe descriptions of social life in Mecca during the last decades of the pre-modern period to two Europeans, Sir Richard Burton, who visited Mecca in 1853 at the time of the pilgrimage, and Christian Snouck Hurgronje, who lived in Mecca for some months during 1884-5. Hurgronje was also an early exponent of photography and with the help of his assistant, al-Sayyid Abd al-Ghaffar, left a photographic record of the topography of the city.

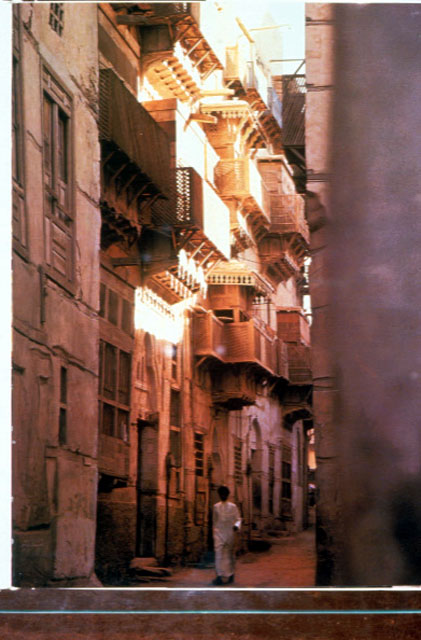

From these descriptions, it can be deduced that life in Mecca was dominated by the institution of pilgrimage and the ceremonies connected with the various holy sites in or near the city. Specific roles concerning the religious rites such as the zamzamiyyun, distributors of water from the well of Zamzam in the courtyard of the Ka‘ba; the Bedouin mukharrijun or camel brokers, providers of transport between Jidda, Mecca, al-Ta’if and Medina; and above all, the mutawwifun, guides for the intending pilgrims who conducted them through the various rites. These mutawwifun had their connections with particular ethnic groups or geographical regions of the Muslim world. Their representative (wukala’) in Jidda would take charge of the pilgrims as soon as they disembarked.

The further history of Mecca down to the coming of the Wahhabis is characterised by the struggle of the Sharifian families amongst themselves and with the Ottoman officials in the town itself or in Jidda. At present, Mecca is part of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Citation:

King, D.A., "Makka." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 2013

http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/makka-COM_0638 [accessed July 2013]

Asani, Ali and Carney E.S. Gavin, ‘Through the Lens of Mirza of Delhi: The Debbas Album of Early-Twentieth-Century Photographs of Pilgrimage Sites in Mecca and Medina.’ In Muqarnas XV: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, Gülru Necipoglu (ed.) (Brill, Leiden: 1998), 178–199.

http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/3202347/Asani_ThroughLens.pdf?sequence=2 [accessed Feb 2014]

Daftary, Farhad, A Short History of the Ismailis (Princeton, NJ: M. Wiener, 1998).

Hunsberger, Alice C., Nasir Khusraw, the Ruby of Badakhshan (London, I. B. Tauris: 2000).

Khoury, Nuha N. N., ‘The Dome of the Rock, the Ka‘ba and Ghumdan: Arab Myths and Umayyad Monuments,’ in Muqarnas X: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, Margaret B. Sevcenko (ed.) (Brill: Leiden, 1993).

http://www.archnet.org/publications/3030 [accessed February 2013]

Wieczorek, Alfried and Claude W. Sui, To the Holy Lands: Places of Pilgrimage from Mecca and Medina to Jerusalem (Munich: Prestel, 2009).

Masjid al-Haram, Aga Khan Museum Collection

http://archnet-uat.cloudapp.net/collections/52/media_contents/87186 [accessed February 2014]