The Fatimids (r. 297-567 AH / 909-1171 CE) established themselves as the Shi‘a caliphate, countering the Abbasids in the 4th AH / 10th CE century. The Fatimids traced their lineage to the Prophet Muhammad through his cousin and son-in-law Ali b. Abi Talib, the first Shi‘i Imam, and his wife Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter.

The Fatimids were also acknowledged as the rightful Imams by the Shi‘a Ismailis not only within their own dominions, but also across many other Muslim lands.

Under the rule of the Fatimids, a dynamic and vibrant Muslim civilisation emerged in the ancient Mediterranean lands, first in North Africa (in the region known as Ifriqiya – present day Tunisia and Algeria) and then in Egypt. Fatimid influence stretched from the shores of the Atlantic to those of the Indian Ocean. The Fatimids emerged as a powerful empire of their time and maintained diverse political and diplomatic relations with the other major empires of the age.

The first Fatimid Imam-Caliph Abdallah al-Mahdi (r. 297-322 AH / 909-934 CE) established his seat in Tunisia. Subsequently, three succeeding Fatimid caliphs, al-Qa‘im, al-Mansur and al-Mu‘izz, lived in North Africa - for a period of sixty-four years between 297-362 AH / 909-973 CE. During this time, they established and maintained a powerful army and navy. The Imam-Caliphs al-Mahdi and al-Mansur founded the cities al-Mahdiyya and al-Mansuriyya, respectively, to the south of Qayrawan, along the Tunisian Coast. In 358 AH / 969 CE, the Imam-Caliph al-Mu‘izz, with the help of his military general Jawhar al-Siqilli acquired Egypt, and laid the foundations of the new city of Cairo, al-Qahira al-Mu‘izzia (the victorious city of al-Mu‘izz).The Fatimid cities of Mahdiya and al-Mansuriya provided a basis for the planning of the city.

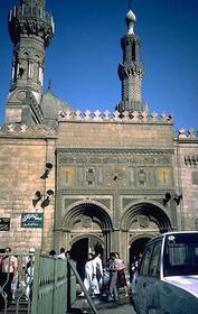

Cairo was designed as a caliphal city comprised of palaces and other administrative buildings. Like the city of Mansuriya, the palace mosque was called al-Azhar (the most radiant), the foundations of which were laid in 359 AH / 970 CE. The two gates of the city were given the same names of Bab Zuwayla (named after the Berber tribe of Zuwayla) and Bab a-Futuh (victory). Cairo had shops, markets, baths, beautiful houses and lofty palaces.

Shortly afterwards, the Fatimid Imam-caliph’s name was pronounced in the sermons at mosques in Mecca and Medina, which confirmed the fact that the Fatimids had replaced the Abbasid caliphs as the protectors of the holy cities of Islam. As the guardians of the Muslim holy cities, the Fatimids ensured the safety and support of pilgrims, not only from Egypt but also from al-Andalus, the Maghreb, Sicily and Syria. They also gave generous pensions to the sharifs of Mecca and Medina. Like Damascus, Baghdad, and Cordoba, Cairo became a major metropolis, linking trade, learning and culture across Muslim and neighbouring lands.

Given the great importance placed on pursuit of knowledge in Islam, the Fatimids strove for excellence in the sphere of “intellectual life”. Their longstanding support for institutions of learning was a reflection of this importance. The mosque of al-Azhar, which was also a centre of learning, the caliphal library, and of the House of Knowledge (Dar al-‘Ilm) established by the Imam-Caliph al-Hakim, attracted scholars from all over the Muslim world.

The 58-year long reign of the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Mustansir bi’llah (r. 428-487 AH / 1036-1094 CE) in Egypt was the longest of any caliph. During this period, difficult challenges arose on several fronts. Egypt suffered from terrible years of famine, drought and plague, beginning around 1060. This resulted in an increase in the price of grain and people were unable to pay their taxes. This in turn meant that the troops could not be paid and a revolt began.

The Fatimids faced one crisis after another. As the Christian kingdoms grew stronger in Spain, Fatimid control over Mediterranean began to weaken. The entry of the Seljuk Turks into Syria also led to a loss of power there. In Egypt, ethnic rivalries broke out between Berbers, Turks, and Sudanese factions in the army leading to in fighting among the soldiers. Eventually, a schism broke out over conflicting claims to the caliphate by al-Mustansir’s elder son Nizar and his younger son al-Must‘ali. Imam Nizar was supported by Ismailis in Persia and Syria. The Persian Ismailis, then under the overall leadership of Hasan-i Sabbah, had already been pursuing an independent policy in Persia. Imam Nizar’s descendants eventually moved to Persia where Nizari Ismailis established their own state based at Alamut and maintained links with the Nizari Ismaili community in Syria and in other regions.

In Cairo, al-Must‘ali became caliph but the Fatimid rule had weakened significantly by then. By the reign of the 11th Fatimid caliph al-Hafiz (r. 526-544 AH / 1131-1149 CE), Fatimid rule became limited to Egypt. The last three caliphs, al-Zafir (r. 544-549 AH / 1149-1154), al-Fa’iz (r. 549-555 AH / 1154-1160) and al-Adid (r. 555-567 AH / 1160-1171) remained under the influence of various military establishments. Finally, upon al-Adid’s death from natural causes at the age of 22 in 567 AH / 1171 CE, Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi, who had been the Fatimid vizier in Cairo since 593 AH / 1169 CE, put an end to Fatimid rule and established the Sunni Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt.

Citation

Daftary, Farhad. “Fatimids.” Encyclopedia Iranica Online, 2012.

http://www.iis.ac.uk/SiteAssets/pdf/Fatimids%20-%20Daftary%20-%20EI%20v%20IX%20p%20423.pdf (an edited version of the original article)

[accessed June 14, 2013]

Daftary, Farhad. Historical dictionary of the Ismailis. (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2012).

Halm, H., The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning, (London: I. B. Tauris, 1997).

Maqrz, Hmad Ibn Al and Shainool Jiwa. Towards a Shii Mediterranean empire. (London: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 2009).

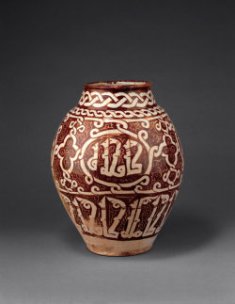

Aga Khan Museum Collection

http://www.akdn.org/museum/collections-search.asp [accessed July 2013]

Fatimid Monuments

http://www.archnet.org/timelines/48/period/Fatimid/year/916 [accessed February 2014]

The Art of the Fatimid Period, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/fati/hd_fati.htm [accessed June 2013]

A Rock Crystal Ewer from Egypt

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/a-rock-crystal-ewer-from-egypt/ [accessed July 2013]

The Tulunids and the Fatimids

http://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/dynasties/tulunids-and-fatimids [accessed May 2013]

Bloom, Jonathan, Arts of the City Victorious, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis, (Princeton, NJ: M. Wiener, 1998).

Daftary, Farhad. Historical dictionary of the Ismailis. (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2012).

“Fatimids” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 2013

http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/fatimids-COM_0218 [accessed June 2013]

Halm, H., The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning, (London: I. B. Tauris, 1997).

http://www.iis.ac.uk/SiteAssets/pdf/REVISED%20COPY%20OF%20Intellectual%20life%20in%20Fatimid%20Times.pdf (A Reading Guide) [accessed Sept 2013]

Hamdani, Sumaiya Abbas. Between revolution and state. (London: I. B. Tauris, 2006).

http://www.iis.ac.uk/SiteAssets/pdf/Between%20Revolution%20and%20State.pdf (A Reading Guide) [accessed Aug 20, 2013]

Jiwa, Shainool. Religious Pluralism in Egypt: the Ahl al-Kitab in Early Fatimid times. An article based on the paper presented at the annual meeting of the Middle East Association of North Ameria, Nov 19, 2001.

http://www.iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp?ContentID=101208 [accessed July 2013]

Maqrz, Hmad Ibn Al and Shainool Jiwa. Towards a Shi‘i Mediterranean Empire. (London: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 2009).

http://www.iis.ac.uk/WebAssets/Large/RG%20TSME%202011%20-%20FINAL%20for%20website%20with%20edits.pdf (A Reading Guide) [accessed June 2013]