An excerpt from the Safar-nama of Nasir Khusraw:

“I found Aleppo to be a nice city. It has a huge rampart, twenty-five cubits I estimated, and an enormous fortress: set on rock as large as the one at Balkh. The whole place is populous and the buildings are built one atop another. This city is a place where tolls are levied on merchants and traders who come and go amongst the lands of Syria, Anatolia, Diyarbekir, Egypt and Iraq.

This city has four gates: the Jews’ Gate, God’s Gate, the Garden Gate and the Antioch Gate. The standard weight used in the market is the Zahriri rotel, which is 480 dirhems. Twenty leagues to the South is Hama and after that Homs. Damascus is fifty leagues from Aleppo; from Aleppo to Antioch is twelve leagues and the same to Tripoli. They say it is two hundred leagues to Constantinople.

On the 11th of Rajab [January 11 1047 CE], we left the city of Aleppo. Three leagues distant was a village called Jund Qinnasrin. The next day, after travelling six leagues, we arrived in the town of Sarmin, which has no fortification walls.

Source: Thackston, W. Wheeler McIntosh, ed. trans., Nasir-i Khusraw’s Book of Travels (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2010), 13-14.

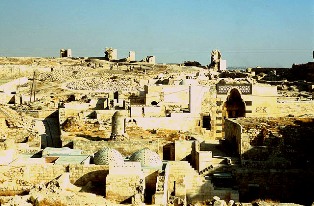

Aleppo or Halab, is an ancient city inhabited continuously from as early as the 2nd millennium BCE. Aleppo is located on a high plateau, halfway between the Mediterranean coast and the Euphrates River, on strategic crossroads between several important trading and pilgrimage routes, including the Silk Road. Aleppo has been ruled by many empires, the most prominent of which are Hittites, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Mongols, Mamluks and Ottomans. Building upon the foundations of the previous empires, each new empire has left its own architectural marks on the city. This makes the core of the "Old City of Aleppo" a historically rich and complex urban fabric.

Aleppo during the Abbasid rule: Aleppo became part of the Muslim world in 637 CE and came to be a prominent regional cultural centre during the Abbasid rule in Syria (r. 750-1258 CE). The city’s landmark citadel was also constructed during this period, upon the ruins of the former Roman acropolis dating to the 9th century BCE. Some of Aleppo’s scholars, such as the poets al-Mutanabbi and Abu Firas al-Hamadani, and philopshers al-Farabi and Ibn Khaldun played a central role in the literary, scientific, philosophical and medical achievements of the Abbasid period.

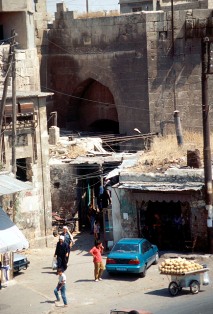

Aleppo during the Seljuk rule: Aleppo was attacked twice during the Crusades in 1098 and 1124 CE, necessitating stronger city defences during unstable political times. Nur al-Din al-Zengi, Syrian prince for the Zengid dynasty under the Seljuk empire, developed the city walls in 1147-1174 CE with towers and fortified gates, eight of which remain today. He also fortified the Citadel and constructed its small mosque. New public institutions in the city were established as well, including a courthouse, central hospital and numerous public bathhouses or hammams. In this period, Aleppo became a main stop for merchants travelling on the Silk Road trade route that extended from the Far East to Europe.

Aleppo during the Ayyubid rule: In 1183 CE, the Ayyubid dynasty gained control of the city. They commissioned construction of a multitude of mosques, religious schools (madrasas) and shrines (mashhads), reasserting Aleppo as a city of religion and piety. The Citadel also underwent major reconstruction and development. By the first decade of the 13th century, under the rule of Ayyubid Sultan al-Zahir al-Ghazi (1186-1216 CE), the Citadel evolved into a palatial city that included residential areas, baths, mosques, shrines, cisterns, granaries, an arsenal, military training grounds, defence towers and a large outer entrance gate.

The aftermath of the Mongol invasion: The Mongolian army attacked Aleppo in 1260 CE, lighting vast fires and killing a large percentage of the population. This weakened Aleppo and the city went under a struggle to regain its status as the regional political and cultural centre. During the 15th century, under Mamluk rule, the city underwent major restoration and reconstruction efforts and re-emerged as a spiritual centre. These developments led to substantial economic growth, making Aleppo a leading Mediterranean exporter of various goods including pistachios, silk, cotton and spices.

Aleppo during the Ottoman rule: By 1517 CE, Aleppo became part of the Ottoman Empire. The city settled into its current position as the major metropolis of northern Syria. The Ottoman rulers established larger khans (caravanserais) and new souks (markets) and hence the city continued to grow as a centre for trade, industry and commerce. The Ottomans also added their signature tall and slender pencil-like minarets to the magnificent mosques built near the Citadel. Towards the end of the Ottoman period, the city began to expand outside its walls and the military role of the Citadel as a defence fortress slowly diminished.

Aleppo during the French Mandate: After the French Mandate (1920 – 1924), Syria began to modernise at a rapid rate. Many middle and upper class old-city residents left their traditional homes to live in residential suburbs that could provide more modern amenities. As more and more people moved from the old city to new residential developments, houses in the city centre were abandoned, rented out to lower-income families or subdivided into smaller units and sold.

In turn, some homes became occupied by migrants from the city’s rural hinterland. This contributed to accelerating the decay of the old city courtyard houses as they were not constructed to withstand such demands. Many former khans were transformed into spaces for storage, becoming hosts for small-scale industrial activity. This commercial activity together with increased traffic congestion also led to an increase in noise, air and water pollution for the residents of these neighbourhoods.

Architecture of Aleppo: The architecture of Aleppo exhibits two significant features—the use of cut stone and a consistent affiliation with the architecture of classical antiquity. These features contribute to its distinctive image and lasting legacy. From the Umayyad period (r. 41-132 AH/ 661-750 CE) up to the 20th century, both the monumental and the residential architecture of Aleppo consistently used cut stone for paving, supports, walls, vaults and even ornaments, giving it a marked sense of solidity and sobriety. The widespread use of stone also seems to have contributed to architectural conservatism. The architecture of Aleppo also retains some significant links with the architecture of classical antiquity, particularly with the Byzantine architecture of North-Western Syria. These include the use of colonnaded courtyards, simplified classical mouldings and the deployment of ornaments as a means to highlight architecture rather than cover it.

Citation:

Tabbaa, Yasser. "Aleppo, architecture ." Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Edited by: Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Brill Online, 2013

http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/aleppo-architecture-COM_23749 [accessed July 2013]

Busquets, Joan ed., “Aleppo: Rehabilitation of the Old City".(Harvard University Graduate School of Design: Cambridge, 2005).

Bianca, Stefano, Syria. Medieval Citadels between East and West (Turin, Italy: Umberto Allemandi for The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, c. 2007).

Daftary, Farhad, A Short History of the Ismailis (Princeton, NJ: M. Wiener, 1998).

Hadjar, Abdallah, Historical Monuments of Aleppo (Aleppo: Automobile and Touring Club of Syria, 2000).

Hunsberger, Alice C., Nasir Khusraw, The Ruby of Badakhshan (London: I. B. Tauris, 2000).

Tabbaa, Yasser, Constructions of Power and Piety in Medieval Aleppo (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997).

Watenpaugh, Heghnar, The Image of an Ottoman City. Imperial Architecture and Urban Experience in Aleppo in the 16th and 17th centuries (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

"An Integrated Approach to Urban Rehabilitation", ed. Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2007. [brochure]

http://archnet-uat.cloudapp.net/sites/6414/publications/7311[accessed February 2014]

Revitalisation of Citadel of Aleppo by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture [video]

http://www.akdn.org/videos_detail.asp?VideoId=6 [accessed July 2013]

Terry Allen, Ayyubid Architecture, Occidental CA 1999.

http://sonic.net/~tallen/palmtree/ayyarch/index.htm [accessed July 2013]