An excerpt from the Safar-nama of Nasir Khusraw:

“To reach the town of Lahsa from any direction, you have to cross vast expanses of desert. The nearest Muslim city to Lahsa that has a ruler is Basrah, and that is one hundred and fifty leagues away. There has never been a ruler of Basrah, however, who has attempted an attack on Lahsa.

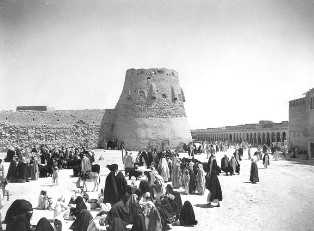

All of the town’s outlying villages and dependencies are enclosed by four strong, concentric walls made of reinforced mud brick. The distance between these walls is about a league, and there are enormous wells inside the town, each the size of five millstones around. All the water of the district is put to use so that none goes outside the walls. A really splendid town is situated inside the fortifications, with all the appurtenances of a large city, and there are more than twenty thousand soldiers.

They said that the ruler had been a sheriff who prevented the people from practicing Islam and relieved them of the obligation of prayer and fasting by claiming that he was the ultimate authority on such matters. His name was Bu-Said, and when you ask the townspeople what sect they belong to, they say they are Busaidis. They neither pray nor fast, but they do believe in Muhammad and his prophecy. Bu-Said told them that he would come among them again after his death, and his tomb, a fine shrine, is located inside the city. He directed that six of his [spiritual] sons should maintain his role with justice and equity and without dispute among themselves until he should come again. Now they have a huge palace that is the seat of state and a throne accommodates all six kings in one place, and they rule in complete accord and harmony. They have also six viziers, and when the kings are all seated on their throne, the six viziers are seated opposite on a bench. Thus all affairs are handled in mutual consultation. At the time I was there they had thirty thousand Zanzibari and Abyssinian slaves working in the fields and orchards.

They take no tax from peasantry, and whenever anyone is stricken by poverty or contracts a debt, they take care of his needs until the debtor’s affairs are cleared up. And if anyone is in debt to another, the creditor cannot claim more than the amount of the debt. Any stranger to the city who possesses a craft by which to earn his livelihood is given enough money to buy the tools of his trade and establish himself, when he repays however much he was given. If anyone’s property or implements suffer loss and the owner is unable to undertake necessary repairs, they appoint their own slaves to make the repairs and charge the owner nothing.

The ruler has several gristmills in Lahsa where the citizenry can have their grain ground into flour for free, and the maintenance of the buildings and the wages of the miller are paid by the rulers. The rulers are called simply “Lord” and the viziers, “counsel.”

There was once no Friday mosque in Lahsa, and the sermon and the congregational prayer were not held. A Persian man, however, named Ali Ibn Ahmad, who was a Muslim, a pilgrim, and very wealthy, built a mosque in order to provide for pilgrims who arrived in the city.

Their commercial transactions are carried out in lead tokens, which are kept in wrappers, each of which is equivalent to six hundred dirhem-weights. When paying for something, they do not even check the wrappers but take them as they are. No one takes this currency outside, however. They also weave fine scarves that are exported to Basrah and other places.

They do not prevent anyone from performing prayers, although they themselves do not pray. The rulers answer most politely and humbly anyone who speaks to him, and wine is not indulged in.

A horse outfitted with collar and crown is kept always tied closely by the tomb of Bu-Said, and a watch is continually maintained day and night for such time as he should rise again and mount the horse. Bu-Said said to his sons, “When I come again among you, you will not recognise me. The sign will be that you strike my neck with my sword. If it be me, I will immediately come back to life.” He made this stipulation so that no one else could claim to be him.

In the time of Baghdad caliphs, one of the rulers attacked Mecca and killed a number of people who were circumambulating the Ka‘ba at the time. They removed the Black Stone from its corner and took it to Lahsa. They said that the stone was a “human magnet” that attracted people, not knowing that it was the nobility and magnificence of Muhammad that drew people there, for the stone had lain there for long ages without anyone paying any particular attention to it. In the end, the Black Stone was brought back and returned to its place.

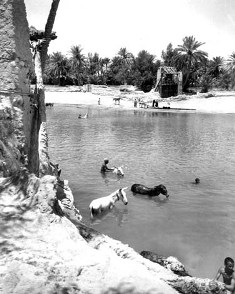

In the city of Lahsa they sell all kinds of animals for meat, such as dog, cat, donkey, cow, sheep, and so on, and the head and skin of whatever animal it is are placed next to the meat so that the customer will know what he is buying. They fatten up dogs, just like grazed sheep, until they are too heavy to walk, and then they are slaughtered and eaten. Seven leagues east of Lahsa is the sea. In this sea is the island of Bahrain, which is fifteen leagues long. There is a large city there and many palm groves. Pearls are found in the sea thereabouts, and half of the divers’ take belongs to the Sultan of Lahsa. South of Lahsa is Oman, which is on the Arabian Peninsula, but three sides face desert that is impossible to cross. The region of Oman is eighty leagues square and tropical. Coconuts, which they call nargel grow there. Directly east of Oman across the sea are Kish and Mukran. South of Oman is Aden, while in the other direction is the province of Fars.

There are so many dates in Lahsa that animals are fattened on and at times more than one thousand maunds are sold for one dinar. Seven leagues north of Lahsa is a region called Qatif, where there is also a large town and many date palms.

An Arab Emir from there once attacked Lahsa, where he maintained siege for a year. One of the fortification walls he captured and wrought much havoc, although he did not obtain much of anything. When he saw me, he asked whether or not it was in the stars for him to take Lahsa, as they were irreligious. I told him what was expedient for me to say, since in my opinion the Bedouin and people of Lahsa were as close as anyone could be to irreligion, people who never performed ritual ablutions from one year to the next. What I record is told from my own experience and far from false rumours, since I was there among them for nine consecutive months, and not at intervals.

I was unable to drink their milk, and whenever I asked for water to drink they offered me milk instead. As I did not take the referred milk and asked for water, they would say, “wherever you see water ask for it there!” In all their lives they had never seen a bath or running water.”

Source: Thackston, W. Wheeler McIntosh, ed. tr., Nasir-i Khusraw’s Book of Travels (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2010), 111–115.

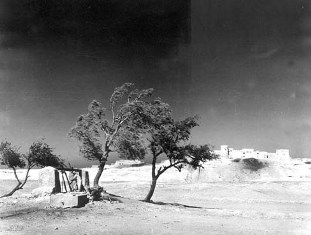

Lahsa (al-Hasa) has been known as a cluster of oases in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Situated between Najd and the Persian Gulf, Lahsa (al-Hasa) was already known in mediaeval times as a stopping-place for caravans. The name al-Hasa (or al-Ahsa) is frequently applied to the Eastern coastal region in general. The most important settlements of Lahsa (al-Hasa) in modern history are al-Hufuf and al-Mubarraz. Lahsa (al-Hasa) has been one of the largest agricultural areas of the Arabian Peninsula, with more than twelve thousand hectares under cultivation and an economy based mainly on date cultivation.

The population has traditionally been divided almost evenly between Sunnis and Itha'asharis (Twelver Shia). Lahsa (al-Hasa) was once an important centre of Maliki learning, and at the beginning of the 4th AH / 10th CE century, the Qarmati movement made its capital there. Lahsa (al-Hasa) was originally a fortress within the historical region of Bahrayn, not far from al-Hajar, the ancient capital of this district. The Qarmati chieftain Abu Tahir al-Janabi founded it in 314 AH / 926 CE. He called the place al-Mu’miniya, but both town and district remained known by the old name of al-Ahsa. Nowadays the capital is known as al-Hufuf although the ancient name al-Ahsa is still in use.

From the 4th–8th century AH / 11th–16th century CE, local tribal dynasties dominated Lahsa (al-Hasa). Ottomans ruled the region from the middle of the 16th century until they were replaced by the tribal Banu Khalid in 1670. In the course of Saudi expansion, Lahsa (al-Hasa) came under their occupation in 1793 and remained in Saudi territory until 1818. Between 1818 and 1844, the Saudis contended with the Egyptian troops of Banu Khalid for supremacy. In 1844, Saudi power was re-established in Lahsa (al-Hasa) but was lost again to Ottomans in 1871. In 1913, Saudis reconquered al-Hasa and since then it has been part of the Saudi kingdom.

Citation

"al-Ahsa’." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill Online.

http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/al-ahsa-SIM_0319 [accessed June 2013]

Al-Rasheed, Madawi. A History of Saudi Arabia (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Facey, William The Story of the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia (London: Stacey International, 1994).

Vidal, Frederico S., The Oasis of al-Hasa (Archive Editions, Farnham Common: 1990).

Hunsberger, Alice C., Nasir Khusraw, the Ruby of Badakhshan (London: I. B. Tauris, 2000).